By his count, Francis J. Greenburger has built or owned more than 20,000 apartments over the past 50 years.

Starting out at age 19 with a five-story brick rental on Barrow Street, Mr. Greenburger built one of the city’s largest co-op conversion businesses in the 1970s and 80s, with projects that included the Delmonico Building, 1045 Park Avenue and the sprawling Clinton Hill Co-ops. Next came Midtown office towers, apartments from New Jersey to Berlin, and even the stray Nova Scotia outlet mall and Tallahassee, Fla., parking garage.

Yet for all of his 20-million-square-foot empire, the project Mr. Greenburger may be most excited about — certainly the one he is most determined to build — is a 25-bed center to treat convicts with mental illnesses.

“These aren’t criminals,” Mr. Greenburger said during an interview last week at his 15th floor office at 55 Fifth Avenue. “These are people who have committed crimes, mostly because they don’t know any better or they are acting out on impulse. And study after study has shown that prison only makes this behavior worse.”

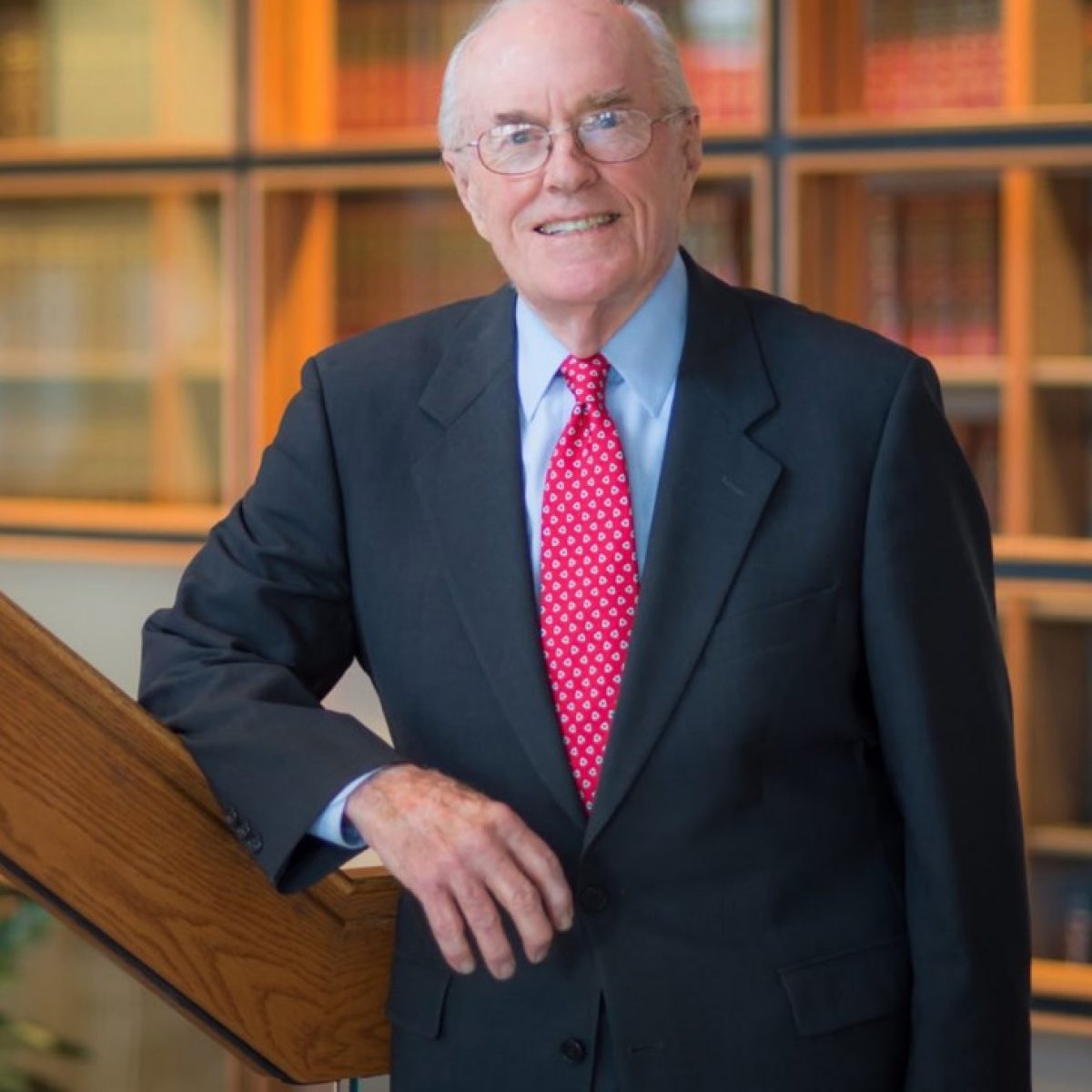

Though he has the bearing of a nightclub bouncer, Mr. Greenburger’s appearance can hardly disguise a voracious intellect. He grew up in Forest Hills, Queens, with parents who pioneered the business of literary translations — Kafka, Sartre, “The Little Prince” — through an agency Mr. Greenburger now manages. The brash businessman and the bespectacled scholar are bound together by an assortment of colorful bow ties.

Mr. Greenburger dropped out of Stuyvesant High School at 15 and moved in with his girlfriend on the Upper East Side. He worked for his parents and managed two bands before he bought the Barrow Street building. Business took off when he started converting those rentals into co-ops, handling more than 10,000 units in 100 buildings over two decades. When the co-op market dried up, he shifted to commercial and industrial buildings, though his top project at the moment is 50 West Street, a 64-story condo tower.

Mr. Greenburger might not seem a natural advocate for prison reform. And that might still be the case were it not for his son, the eldest of his four children.

In 2010, Mr. Greenburger’s son, then 18 years old, was arrested on suspicion of trying to rob a cab with a friend. When his father later asked him why, his response was, according to Mr. Greenburger, “Because I needed money.”

“He was five minutes from my office. I told him if he ever needs anything, anything, just ask, and he said, ‘Yeah, but I needed the money right now,’ ” Mr. Greenburger said. “What was really going on is, his greatest need, because of his mental condition, was socialization. He was just going along with his friend. He can’t help himself.”

The son has struggled throughout his life, and has received at least a half-dozen diagnoses, including oppositional defiant disorder and autism. “It depended on the doctor and the day,” Mr. Greenburger said. The family tried to place him in mainstream classes in school, but he was always in trouble. His behavior worsened after his mother died of cancer, leading to a succession of schools for students with special needs. He then went to work for his father in a part-time janitorial position.

It was on his way home one day, about a year after the first incident, that his son became convinced he was being followed by a drug dealer. During frantic phone calls, Mr. Greenburger begged him to wait for his live-in aides. Instead, his son called the police, who ignored him, according to Mr. Greenburger.

“He didn’t know what to do, so he gathered up whatever trash he could find around the apartment, set it on the stove and started a fire,” Mr. Greenburger said. “Then he called the Fire Department, thinking they could protect him.”

Instead, he was arrested and charged with arson.

Mr. Greenburger had been researching the criminal justice system and learned how detrimental it could be for the mentally ill. He began pleading with the district attorney for alternatives, and the district attorney responded that if Mr. Greenburger could find a secure treatment center for his son, he would consider placing him there instead of prison.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but he was sending me on a wild-goose chase,” Mr. Greenburger said. “There were literally none.”

So he has decided to build one of his own.

The Greenburger Center for Social and Criminal Justice is not likely to benefit his son, at least not directly, as he is halfway through a five-year prison sentence at the Cayuga Correctional Facility outside Syracuse. But the center, which is envisioned as a think tank and a treatment facility, has even greater ambitions: to cut the United States incarceration rate of 2.3 million in half over the next decade.

This involves advocacy campaigns and lobbying, including for sentencing reforms and the decriminalization of drugs. But its main focus is the establishment of better mental health treatment for inmates in the United States, starting with that 25-bed pilot facility. Mr. Greenburger has identified some vacant institutional properties in the metropolitan area but has not settled on a site. The project, which would serve as an alternative to incarceration, would require numerous state approvals.

“I know he wants it open next year — he’s a developer — but realistically, we’re shooting for 2016,” said Cheryl Roberts, a former corporation counsel for Hudson, N.Y., who is the center’s new executive director.

The center would offer a voluntary program for people who can demonstrate a connection between their crimes and their mental health issues. They would go through treatment, with an emphasis on group therapies, for one to three years. Convicts would have to consent to going, but once they were in, they could not leave. Most existing facilities do not keep patients on lockdown.

“There used to be numerous facilities like this, but now no one is doing what they’re trying to do,” said Jeremy Travis, president of John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Mr. Greenburger hopes his efforts could someday extend beyond prison walls to preventing the commission of crimes.

“If you look at all the shootings and such, where parents and family said they had nowhere to go, no one to turn to,” he said. “I think we’re beginning to realize that the pendulum maybe swung too far away from mental institutions, and we need this third way.”