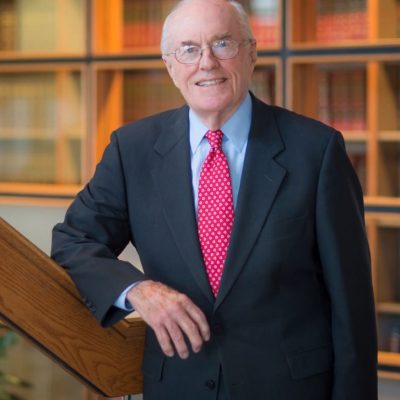

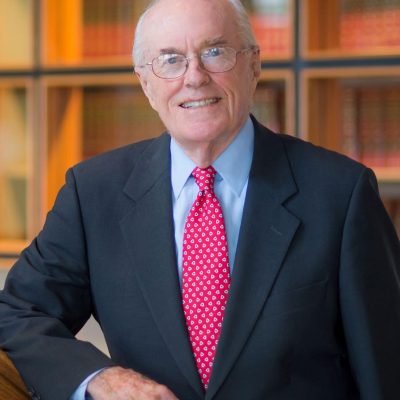

The New York Daily News featured an Op Ed by Len Elmore, retired basketball player, lawyer, sports commentator and Greenburger Center Board of Advisor. Elmore’s Op Ed follows:

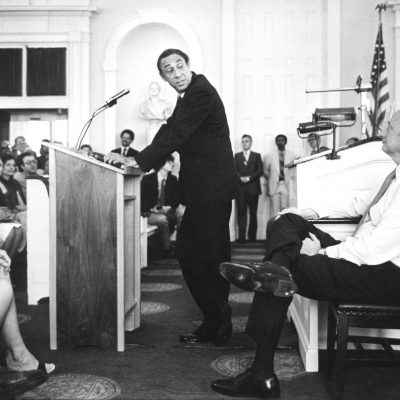

It was a striking sight: Four of New York City’s five district attorneys gathered earlier this month at a forum sponsored by the Daily News, Greenburger Center and Metro-IAF to discuss their approaches to stemming the mass incarceration of people with mental illness and substance use disorders, in light of plans to shrink and eventually close jails on Rikers Island.

I was positively impressed by the change in attitude and the level of resources dedicated to tackling the needs of those with mental illness or addictions since the days when I served as an assistant district attorney for Brooklyn DA Elizabeth Holtzman in the late 1980s.

As an African-American who grew up in New York City, when I left the New York Knicks to pursue a law degree, I planned to begin my legal career as a public defender. Like many lawyers of color of my generation, our ideas about the role of lawyers were forged in the search and struggle for justice by blacks and other victims of the system and by progressive thinkers.

Many of us believed that the law could ignite societal change, and I was drawn to the work of public defenders and social service lawyers who helped the poor, the wrongly convicted or those otherwise charged with crimes unsupported by the facts in the case.

My perspective changed during my third year at Harvard Law School, when I participated in a public defender program. I realized then that circumstances often forced public defenders to operate from a reactive posture, while prosecutors set the tone, drove the cases and made life-changing decisions daily, with enormous and lasting impact on society. Why wouldn’t I then, as I have advised so many young attorneys of color to do since, work from a proactive position as a prosecutor to drive a just change?

While DAs Darcel Clark, Cy Vance Jr., Eric Gonzalez and Michael McMahon certainly seem to be driving change and inspiring each other to take even bolder steps, my experience working in a DA’s office demonstrated it is not enough for a DA to express progressive policies publicly. Real, systemic cultural change requires the attorneys on the front lines — assistant district attorneys — as well as their supervisors to be acknowledged and rewarded for proactively putting those policies into practice.

Equally important, truly changing office culture means assistant district attorneys need cultural competence and training to understand the circumstances of the people they prosecute. To really effect justice, these line assistants must prosecute without cultural or racial biases and with a visceral understanding of the communities they serve. In this era, that understanding must include the impact of mental illness and substance use disorders on conduct.

Most line assistants during my tenure in Kings County had not grown up in Brooklyn or even in an urban area and had limited understanding of the needs of the communities they served or the realities of addiction. It was not uncommon to observe some colleagues charging defendants who cycled through the office on low-level drug charges with misdemeanors, seeking a maximum year of jail time to “teach them a lesson.”

Even in the office run by Holtzman, one of New York’s most progressive DAs ever, assistants taking early steps to treat a repeat low-level drug offender as an addict instead of a hardened criminal were often not credited or meaningfully recognized for exercising discretion in seeking an alternative to incarceration. This longer-term protective view for the community by these assistants went unrewarded and sometimes ignored.

If New York is to close Rikers, as it must, and continue to reduce incarceration rates citywide, the innovative programs discussed by the four DAs must be implemented from the ground up by assistant DAs who understand the critical role prosecutors play in the criminal justice system. Doing justice means more than being tough on crime. It means recognizing when a crime is really an addiction or a mental illness and how to distinguish between youthful indiscretion or response to trauma from true criminality.

I urge the DAs to proactively promote a culture that emboldens assistants through incentives and recognition to do real justice rather than merely convict and default to the corrections system. The progressive approach by big-city district attorneys in separating the treatment of mental disorder and addiction from criminally culpable conduct is only as effective as the line ADAs who confront these issues daily.

Elmore is a retired basketball player, lawyer and sports commentator. He serves on the board of advisers to the Greenburger Center for Social and Criminal Justice, a nonprofit seeking alternatives to incarceration.